|

Profiles > Philosophy > Ludwig Wittgenstein

|

| Ludwig Wittgenstein |

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) was an Austrian/British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of the mind, and the philosophy of language. From 1939-1947, Wittgenstein taught at the University of Cambridge. During his lifetime he published just one slim book, the 75-page Tractatus LogicoPhilosophicus (1921), one article, one book review and a children's dictionary. His voluminous manuscripts were edited and published posthumously. Philosophical Investigations appeared as a book in 1953 and by the end of the century it was considered an important modern classic.

Philosopher Bertrand Russelldescribed Wittgenstein: the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived; passionate, profound, intense, and dominating.

|  |

|

| Born |

26 April 1889 / Vienna |

| Died |

29 April 1951/ Cambridge |

| Nationality |

Austrian |

| Era |

20th Century Philosophy |

| School |

Analytic Philosophy |

| Main Interests |

Logic, Metaphysics, Philosophy of Language, Philosophy of Mathematics |

| Notable Ideas |

Picture theory of Language, Truth Functions, States of Affairs, Logical Necessity, Language Games |

|

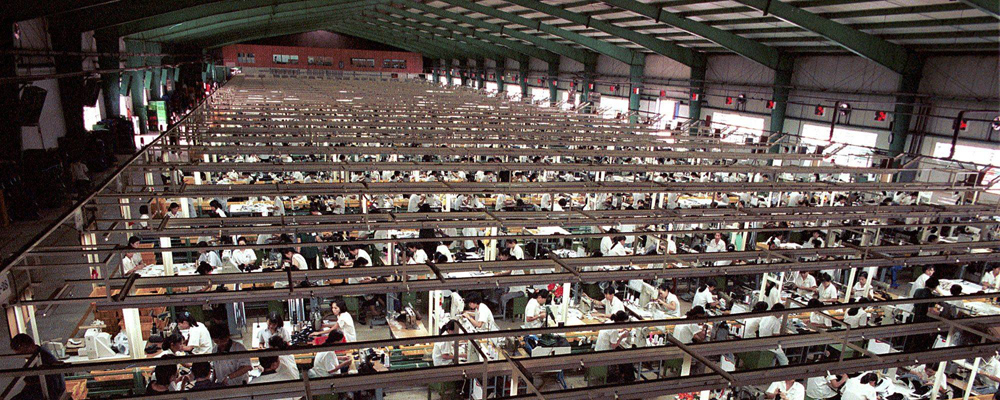

According to a family tree prepared in Jerusalem after World War II, Wittgenstein's paternal great-grandfather was Moses Meier, a Jewish land agent who lived with his wife, Brendel Simon, in BahdLaasphe in the Principality of Wittgenstein, Westphalia. In July 1808, Napoleon issued a decree that everyone, including Jews,must adopt an inheritable family surname, and so Meier's son,also Moses, took the name of his employers, the Sayn-Wittgensteins, and became Moses Meier Wittgenstein. His son,Hermann Christian Wittgenstein -- who took the middle name "Christian" to distance himself from his Jewish background -- married Fanny Figdor, also Jewish, who converted to Protestantism just before they married, and the couple founded a successful business trading in wool in Leipzig. Ludwig's grandmother, was a first cousin of the famous violinist Joseph Joachim. They had 11 children -- among them Wittgenstein's father. Karl Wittgenstein (1847-1913) became an industrial tycoon, and by the late 1880s was one of the richest men in Europe, with an effective monopoly on Austria's steel cartel. Thanks to Karl, the Wittgensteins became the second wealthiest family in Austria/Hungary, behind only the Rothschilds. As a result of his decision in 1898 to invest substantially |

|

overseas, particularly in the Netherlands, Switzerland and the US, the family was to an extent shielded from the hyper-inflation that hit Austria in 1922. Their wealth did still diminish due to post-1918 hyper-inflation and the Great Depression, although even as late as 1938 they owned 13 mansions in Vienna alone.

|

|

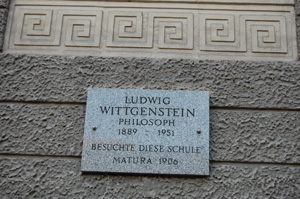

Wittgenstein was taught by private tutors at home until he was fourteen years old. Subsequently, for three years, he attended a school. After the deaths of Hans and Rudi, Karl relented, and allowed Paul and Ludwig to be sent to school. Waugh writes that it was too late for Wittgenstein to pass his exams for the more academic Gymnasium in Wiener Neustadt -- having had no formal schooling, he failed his entrance exam and only barely managed after extra tuition to pass the exam for the more technically oriented K.u.k. Realschule in Linz, a small state school with 300 pupils. In 1903, when he was 14, he began his three years of formal schooling.Ludwig lodged nearby with the family of Dr. Srigl, a master at the local gymnasium, and the family gave him the nickname Luki.

On starting at Realschule, Wittgenstein was moved forward a year. Historian Brigitte Hamann writes that he stood out from the other boys -- he spoke an unusually pure form of High German with a stutter, dressed elegantly, and was sensitive and unsociable. He had particular difficulty with spelling and failed his written German exam because of it. He wrote in 1931: My bad spelling in youth, up to the age of about 19, is connected with therest of my character.

|

|

|

| Jewish background and Hitler:

|

|

| There is much debate about the extent to which Wittgenstein and his siblings, who were of 3/4 Jewish descent,saw themselves as Jews, and the issue has arisen in particular regarding Wittgenstein's schooldays, because Adolf Hitler was at the same schoolduring (part of) the same time. Laurence Goldstein argues it is "overwhelmingly probable" the boys met each other and that Hitler would have disliked Wittgenstein -- a stammering, precocious,precious, aristocratic upstart. Other commentators have dismissed as irresponsible and uninformed any suggestion that Wittgenstein's wealth and unusual personality may have fed Hitler's anti-semitism, in part because there is no indication that Hitler would have seen Wittgenstein as Jewish. |

|

| Wittgenstein and Hitler were born just six days apart, though Hitler had been held back a year, while Wittgenstein was moved forward by one, so they ended up two grades apart at Realschule. Monk estimates they were both at the school during the 1904-1905 school year, but says there is no evidence they had anything to do with each other.Several commentators have argued that a school photograph of Hitler may show Wittgenstein in the lower left corner, but Hamann says the photograph stems from 1900 (or 1901), before Wittgenstein's time.In his own writings,Wittgenstein frequently referred to himself as Jewish, at times as part of an apparent self-flagellation. For example, while berating himself for being a "reproductive" as opposed to "productive" thinker, he attributed this to his own Jewish sense of identity, writing: The saint is the only Jewish genius. Even the greatest Jewish thinker is no more than talented. While Wittgenstein would later claim that my thoughts are 100% Hebraic,as Hans Sluga has argued -- his was a self-doubting Judaism, which had always the possibility of collapsing into a destructive self-hatred but which also held immense promise of innovation and genius. |

|

| World War I and the Tractatus

|

|

| Karl Wittgenstein died on 20 January 1913, and after receiving his inheritance, Wittgenstein became one of the wealthiest men in Europe. He donated some of his money, at first anonymously, to Austrian artists and writers,including Rainer Maria Rilke and Georg Trakl. Wittgenstein came to feel that he could not get to the heart of his most fundamental questions while surrounded by other academics, and in 1913 he retreated to the village of Skjolden in Norway, where he rented the second floor of a house for the winter. He later saw this as one of the most productive periods of his life, writing Logik (Notes on Logic), the predecessor of Tractatus. While in Norway,Wittgenstein learned Norwegian so that he could converse with the local villagers, and Danish in order to read the works of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. |

|

| At Wittgenstein's insistence, Moore, who was now a Cambridge fellow, visited him in Norway in 1914, albeit reluctantly as Wittgenstein exhausted him. David Edmonds and John Eidinow wrote that Wittgenstein regarded Moore, an internationally-known philosopher, as an example of how far someone could get in life with absolutely no intelligence whatever.In Norway it was clear that Moore was expected to act as Wittgenstein's secretary, taking down his notes, with Wittgenstein falling into a rage when Moore got something wrong. When he returned to Cambridge, Moore asked the university to consider accepting Logik as sufficient for a bachelor's degree, but they refused, saying it wasn't formatted properly and was missing footnotes. Wittgenstein was furious, writing to Moore in May 1914: If I am not worth your making an exception for me even in some stupid details then I may as well go to Hell directly; and if I am worth it and you don't do it then -- by God -- you might go there. Moore was apparently distraught; he wrote in his diary that he felt sick and could not get the letter out of his head. The two did not speak again until 1929.

|

|

| In the summer of 1918 Wittgenstein took military leave and went to stay in one of his family's Vienna summer houses, Neuwaldegg. It was there, in August 1918, that he completed the Tractatus, which he submitted with the title Der Satz to the publishers Jahoda and Siegel. A series of events around this time left him deeply upset. On August 13, his uncle Paul died. On October 25, he learned that Jahoda and Siegel had decided not to publish the Tractatus, and on October 27, his brother Kurt killed himself, the third of his brothers to commit suicide. It was around this time he received a letter from David Pinsent's mother to say that Pinsent had been killed in a plane crash on May 8. Wittgenstein was distraught to the point of being suicidal. He was sent back to the Italian front after his leave and, as a result of the defeat of the Austrian army, was captured by Allied forces on November 3 in Trentino. He subsequently spent nine months in an Italian prisoner of war camp.He returned to his family in Vienna on 25 August 1919 -- by all accounts physically and mentally spent. He apparently talked incessantly about suicide, terrifying his sisters and brother Paul. He decided to do two things: to enroll in teacher training college as an elementary school teacher, and to get rid of his fortune. In 1914, it had been providing him with an income of 300,000 Kronen a year, but by 1919 was worth a great deal more, with a sizeable portfolio of

|

|

|

investments in the United States and the Netherlands. He divided it among his siblings, except for Margarete,insisting that it not be held in trust for him. His family saw him as ill, and acquiesced.

|

|

|

|

While Wittgenstein was living in isolation in rural Austria, the Tractatus was published to considerable interest, first in German in 1921 as Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung, part of Wilhelm Ostwald's journal Annalen der Naturphilosophie, though Wittgenstein was not happy with the result and called it a pirate edition. Russell had agreed to write an introduction to explain why it was important, because it was otherwise unlikely to have been published: it was difficult if not impossible to understand, and Wittgenstein was unknown in philosophy.An English translation was prepared in Cambridge by Frank Ramsey, a mathematics undergraduate at King's commissioned by C. K. Ogden. It was Moore who suggested Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus for the title, an allusion to Baruch Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. Initially there were difficulties in finding a publisher for the English edition, because Wittgenstein was insisting it appear without Russell's introduction; Cambridge University Press turned it down for that reason. Finally in 1922 an agreement was reached with Wittgenstein that Kegan Paul would print a bilingual edition with Russell's introduction and the Ramsey-Ogden translation. This is the translation that was approved by Wittgenstein, but it is problematic in a number of ways. Wittgenstein's English was poor at the time, and Ramsey was a teenager who had only recently learned German, so philosophers often prefer to use a 1961 translation by David Pears and Brian McGuinness.An aim of the Tractatus is to reveal the relationship between language and the world: what can be said about it, and what can only be shown. Wittgenstein argues that language has an underlying logical structure, a structure that provides the limits of what can be said meaningfully, and therefore the limits of what can be thought. The limits of language, for Wittgenstein, are the limits of philosophy. Much of philosophy involves attempts to say the unsayable: What we can say at all can be said clearly, he argues. Anything beyond that -- religion, ethics, aesthetics, the mystical -- cannot be discussed. They are not in themselves nonsensical, but any statement about them must be. He wrote in the preface: The book will, therefore, draw a limit to thinking, or rather -- not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts; for, in order to draw a limit to thinking we should have to be able to think both sides of this limit -- we should therefore have to be able to think what cannot be thought.

Wittgenstein began work on his final manuscript, MS 177, on 25 April 1951. It was his 62nd birthday on 26 April. He went for a walk the next afternoon, and wrote his last entry that day, 27 April. That evening, he became very ill;when his doctor told him he might live only a few days, he reportedly replied, "Good!" Joan stayed with him throughout that night, and just before losing consciousness for the last time on 28 April, he told her: Tell them I've had a wonderful life. Norman Malcolm described this as a strangely moving utterance.

|

|

Credits

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludwig_Wittgenstein

www.iep.utm.edu/wittgens

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/wittgenstein

Wittgenstein's Place in Twentieth-century Analytic Philosophy, Hacker (1996)

|

|